The Logic of VFX Compositing

The Logic of VFX Compositing isn’t some secret formula hidden away in dusty manuals. It’s more like the unspoken rules, the fundamental ‘why’ behind everything we do when we’re piecing together images to create something new, something that hopefully fools your eye into thinking it’s all real. Think of it as the common sense that guides the magic trick.

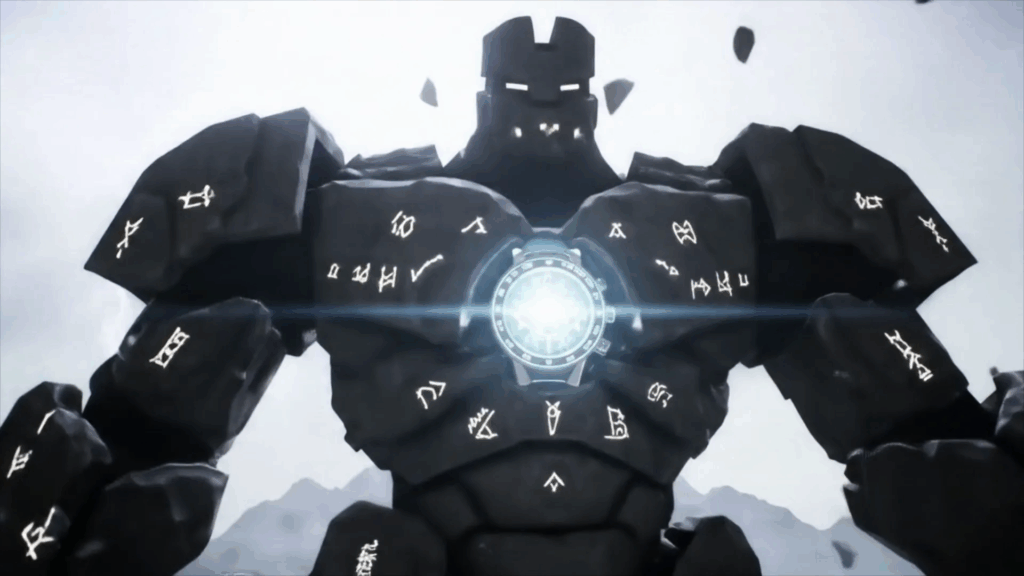

For years now, I’ve been knee-deep in the world of visual effects, specifically on the compositing side. That’s the part where we take all the different pieces – the footage shot on set, the stuff built in 3D, maybe some matte paintings or special effects elements – and glue them all together seamlessly. When you see a superhero flying, a dragon breathing fire, or a character walking through a scene that was actually shot months apart from them, that’s compositing. And at the heart of making it work, of making it *believable*, is understanding The Logic of VFX Compositing.

It’s not just about knowing which buttons to press in the software. Trust me, you can know every shortcut and feature, but if you don’t grasp the underlying principles, you’ll just end up with a messy collage instead of a convincing illusion. It’s about understanding light, shadow, color, perspective, and how things behave in the real world, and then applying that understanding when you’re building your digital image. It’s about problem-solving, pure and simple, guided by The Logic of VFX Compositing.

Breaking Down the “Why”

So, what *is* this logic? At its core, it’s about integration. Our job is to make disparate elements look like they were always part of the same shot. This requires thinking about the image in terms of layers, yes, but more importantly, in terms of how those layers interact and influence each other. It’s about understanding how to blend things together so the edges disappear, the lighting matches, and the colors feel right. It’s detective work, really. You look at the original footage, the ‘plate’, and you analyze everything – the direction of light, the quality of shadows, the atmosphere, the grain or noise, the lens distortion. Then, when you get a new element to add, you know exactly what it needs to match those qualities. That’s The Logic of VFX Compositing in action.

It’s not just about making things look pretty; it’s about making them obey the same physical rules as the original photography. If the plate has soft shadows because the light source was large and diffuse, your added element needs soft shadows too. If the plate was shot with a wide-angle lens that distorts the edges, your element might need similar distortion to feel like it’s in the same space. This might sound obvious, but it’s surprising how often shots fail because these fundamental logical rules aren’t followed.

This is why understanding the foundational principles is so much more valuable than just learning a specific tool. Tools change, software gets updated, but the principles of how light works, how colors blend, and how to create depth and realism? That stuff is timeless. It’s the bedrock upon which all The Logic of VFX Compositing is built.

Understanding Light and Shadow

The Building Blocks: Layers and Channels

Most compositing software, whether it uses a layer-based system like After Effects or a node-based system like Nuke or Fusion, relies on breaking down the image into different components. At the most basic level, you have color information (Red, Green, Blue channels) and often, transparency information (the Alpha channel). Understanding these channels is absolutely fundamental to The Logic of VFX Compositing.

Think of the Alpha channel like a stencil. It tells you which parts of your image are solid and which parts are completely see-through, or even semi-transparent. When you combine images, the Alpha channel of the element you’re adding dictates how much of it shows up and how much of the background shows through. Getting a clean, accurate Alpha channel is often one of the biggest challenges in compositing, especially when you’re dealing with tricky things like hair, motion blur, or semi-transparent objects like glass or smoke. The logic here is simple: if your Alpha is messy, your edges will look bad, and the element won’t blend convincingly.

Then there’s the concept of premultiplication. Okay, this sounds a bit technical, but the *logic* behind it is crucial for avoiding ugly halos or dark edges around your composited elements. When you have an image with transparency (an Alpha channel), the color information (RGB) might already have that transparency ‘baked in’. This is ‘premultiplied’. If it doesn’t, it’s ‘unpremultiplied’ or ‘straight’. When you combine these images, they need to be handled consistently. The logic is about how you multiply the color information by the alpha information correctly so that semi-transparent areas blend correctly with the background, rather than leaving behind weird fringing. It’s a detail, but a detail that screams “fake” if you get it wrong. Understanding this interaction is a key part of mastering The Logic of VFX Compositing.

This whole idea of channels extends beyond just RGB and Alpha. In modern VFX, we often work with ‘multi-channel’ EXR files. These files can contain tons of information about the 3D scene that generated an element: Z-depth (how far away things are), Normals (which way surfaces are facing), position data, different light passes (how much light hits the object from different sources), and so on. The logic of using these channels is that they give us incredible control in compositing. Instead of just getting a flat image of a 3D object, we get all the raw data, allowing us to manipulate its lighting, its distance, or even create complex masks based on its properties, all within the compositing software. This gives us flexibility and creative control, all thanks to understanding how to utilize this rich channel data, which is a powerful application of The Logic of VFX Compositing.

Mattes and Masks: The Art of Isolation

A huge part of The Logic of VFX Compositing revolves around isolation. We constantly need to isolate specific parts of an image to work on them. This is where mattes and masks come in. A mask is essentially a grayscale image that tells us what parts of another image are visible (white), invisible (black), or semi-transparent (shades of gray). Mattes are often generated automatically (like from a green screen key), while masks are often drawn manually or created from other channels.

Think about needing to change the color of just one specific object in a shot, or maybe blur only the background while the foreground stays sharp. You need a mask or a matte for that object or background. The logic here is precision. You only want to affect exactly what you intend to affect. Creating clean, accurate mattes is a skill in itself. Rotoscoping, the process of manually drawing masks around moving objects frame by frame, is often painstaking work, but it’s essential when you don’t have a green screen or automated way to isolate something. The logic of rotoscoping is creating a shape that follows the object’s movement perfectly, providing a clean matte to use in your composite.

Keying, on the other hand, is using color information to create a matte, most commonly with green or blue screens. The logic of keying is to use the distinct color of the screen to automatically separate the foreground subject. It sounds simple, but things like color spill (the green light bouncing back onto the subject), wrinkles in the screen, or motion blur can make it tricky. A skilled compositor understands the logic of refining a key – often using multiple keyers or combining keyer mattes with rotoscoping or other masking techniques – to pull a perfect matte with clean edges, especially around notoriously difficult areas like hair.

There are also garbage mattes (rough masks to cut away the unnecessary parts outside your subject, saving processing power), core mattes (solid mattes of the main shape), and edge mattes (fine mattes for detailed areas like hair). Understanding *when* and *why* to use each type of matte, and how to combine them effectively, is a key part of mastering The Logic of VFX Compositing. It’s all about having the right tool (or matte) for the job to get the cleanest possible separation.

Tracking and Motion: Making Things Stick

Often, the things we add to a shot need to move exactly like the camera or like another object in the scene. This is where tracking comes in. Tracking is the process of analyzing the movement in the original footage and extracting that motion data so we can apply it to our added elements. The logic here is about mimicking reality. If the camera is panning and tilting, your spaceship or your piece of text needs to pan and tilt at the exact same rate to look like it’s part of the scene.

There are different kinds of tracking. 2D tracking follows points or patterns in a flat image, useful for sticking a graphic onto a wall or replacing a screen on a phone that isn’t changing perspective much. 3D tracking (often called matchmove) is more complex. It analyzes the footage to recreate the camera’s movement and the 3D space of the scene. This is what you need to convincingly add a 3D character or a set extension that needs to stay fixed in the scene as the camera moves around. The logic of 3D tracking is essentially reversing the camera’s motion picture process to figure out where the camera was in 3D space at every given moment, allowing us to place new objects into that same space.

Getting good tracks is often challenging. Things like motion blur, changes in lighting, or objects passing in front of your tracking markers can mess things up. A good compositor understands the logic of choosing the right tracking points, analyzing tracking errors, and knowing when a manual tweak or a different tracking method is needed. Once you have solid tracking data, applying it correctly to your added elements is another step that requires understanding The Logic of VFX Compositing – making sure the pivot points are correct and the motion is applied in a way that matches the original move.

Motion blur is another critical aspect. In the real world, if something moves fast relative to the camera’s shutter speed, it appears blurred. Your added elements need to obey this same rule. Compositing software can generate motion blur based on the tracking data and the element’s movement. The logic here is realism; static elements in a moving shot look fake. Adding accurate motion blur makes the composite feel physically correct and helps blend the element into the live-action plate.

Integrating Light and Color

This is arguably one of the most important and nuanced parts of The Logic of VFX Compositing: making the new elements look like they were lit by the same lights and exist in the same atmospheric and color environment as the original plate. You can have a perfectly tracked, perfectly matted element, but if the lighting and color don’t match, it will stick out like a sore thumb.

Look at the original plate. Where is the main light coming from? Is it hard and direct (like sunlight)? Is it soft and diffuse (like an overcast day or indoor lighting bouncing around)? Are there multiple light sources? What color are they (warm sunset light, cool fluorescent light)? How do they affect shadows (sharp edges, soft edges, color in the shadows)? Understanding these characteristics of the plate’s lighting is step one. The logic is to recreate those characteristics on your added element.

If you’re adding a 3D element, the 3D artists should ideally light it to match the plate. But in compositing, we often need to refine this or add additional lighting effects. We can use techniques like ‘light wraps’ (where light from the background appears to wrap around the edges of the foreground object) or subtle glows and reflections to integrate elements convincingly. The logic here is making the element feel physically present in the scene’s lighting setup.

Color is just as critical. Your added element needs to have the same color temperature, contrast, and overall color cast as the plate. Is the plate slightly warm? Does it have a greenish tint in the shadows? Your element needs to match that. This involves careful color correction. You analyze the blacks, whites, and mid-tones of the plate and the element, using tools like color pickers and scopes to make objective comparisons, not just relying on your eye (though your eye is crucial too!). The logic of color correction in compositing is matching the color relationships and overall feel of the plate, ensuring consistency across all elements.

This isn’t just about making things look the same; it’s also about depth. Atmospherics like fog, haze, or dust affect how light and color behave over distance. Objects further away appear less saturated, less contrasted, and take on the color tint of the atmosphere. Adding these subtle atmospheric effects to your composite, often using things like Z-depth passes from 3D or painting them in 2D, is another application of The Logic of VFX Compositing to create a sense of depth and realism.

Sometimes, the lighting and color integration is the longest, most iterative process in a shot. You tweak the levels, adjust the curves, add a subtle color shift, look at it again, realize it’s still not quite right, and go back. It requires a keen eye and a deep understanding of how light and color interact in the real world and how to mimic that digitally. This relentless pursuit of matching reality is central to The Logic of VFX Compositing.

Color Matching for Compositing

Handling Edges and Blending Modes

Those pesky edges! They are often the biggest giveaway that a shot is a composite. Whether it’s a slightly-too-sharp edge from a key, a halo around a rotoscoped element, or just a general lack of integration, bad edges ruin the illusion. The Logic of VFX Compositing dictates that edges need to feel natural and consistent with the rest of the image.

This involves several techniques. We already talked about getting a good matte, which is the first step. But often, you need to refine the edge of the matte itself. This might involve softening it slightly (but not too much!), adding a tiny bit of “choke” (shrinking the matte slightly) or “spread” (expanding it), or using sophisticated tools that help manage semi-transparent pixels along the edge, like hair or fur. The logic is to make the transition between the foreground and background seamless, without hard lines or visible fringing.

Blending modes are another key tool, particularly in layer-based software. These modes determine how the pixels of one layer interact with the pixels of the layer below it based on their color values. Modes like ‘Screen’ are great for adding glows or magical effects (they generally lighten the image), while ‘Multiply’ is useful for shadows or darkening effects. ‘Overlay’ or ‘Soft Light’ are good for color correction or adding subtle textures. Understanding the logic of how each blending mode affects the underlying pixels is crucial for using them effectively to integrate elements or create specific looks.

For instance, adding smoke or atmosphere often involves using blending modes like ‘Screen’ or ‘Add’ because smoke tends to lighten the area it occupies and doesn’t fully obscure what’s behind it. Adding a shadow might use ‘Multiply’ or a custom setup that darkens only the areas the shadow falls on, based on the luminance of the background. The logic is using the mathematical operation of the blending mode to simulate a real-world optical effect.

The Logic of VFX Compositing around edges also involves details like grain and noise matching. Film stock has grain, digital cameras produce noise. Your added element won’t have the exact same grain/noise unless you add it. Analyzing the grain/noise pattern of the plate and then adding a matching pattern to your element is vital for integration. It helps the element feel like it was captured by the same camera under the same conditions. It’s a subtle detail, but one that contributes significantly to the overall realism and is a prime example of applying The Logic of VFX Compositing at a micro level.

Workflow and Problem Solving

Compositing isn’t just a collection of techniques; it’s also a workflow, a logical sequence of operations. While every shot is different, there’s usually a logical order to approach things that makes the process more efficient and manageable. Typically, you start with plate preparation (cleaning up unwanted objects, stabilizing shaky footage). Then you move to isolating your elements (keying, roto). Next comes tracking and matching motion. After that, it’s integration – lighting, color, shadows, reflections, atmospherics. Finally, you add the finishing touches like grain, lens effects, and overall color grading for the shot.

This ordered approach is part of The Logic of VFX Compositing. Why do you do plate prep first? Because you want a clean base to work on. Why integrate lighting and color after isolating elements? Because you need the elements separated to adjust them properly. Why add grain at the end? Because you want it applied consistently to the final combined image, not added individually to elements before they’re integrated.

Problem-solving is also a huge part of the job, and it relies heavily on The Logic of VFX Compositing. When something looks wrong, you have to figure out *why*. Is the lighting off? Is the color mismatched? Is the edge bad? Is the motion not sticking? You isolate the problem area and apply the logical steps to fix it. If the color is wrong, you look at the plate’s colors, compare them to the element’s colors, and adjust using color correction tools. If the edge is bad, you examine the matte and see if it needs refining. This systematic, logical approach to troubleshooting is what separates experienced compositors from beginners.

Sometimes the solution isn’t obvious, and that’s where creativity meets logic. You might need to invent a workaround, like using an unexpected combination of tools or creating a custom element to fix a problem in the plate. But even these creative solutions are guided by the underlying Logic of VFX Compositing – the need to maintain realism, consistency, and seamless integration.

One long paragraph to demonstrate the depth of logical thinking involved in a typical tricky shot:

Imagine you have a shot where a character is walking in front of a green screen, and you need to replace the screen with a busy street scene filmed on location, but the character is wearing a green shirt, and there’s a lot of motion blur because they’re running, and the original plate of the street scene has lens flares and dust motes. The Logic of VFX Compositing kicks in immediately as you analyze the challenge. First, you look at the green screen footage. The green shirt is a problem for standard keying. The motion blur means the edges will be soft and potentially pull partial transparency on the character where they should be solid. The street plate has its own characteristics – specific lighting, atmosphere, lens artifacts – that your character element needs to match. So, the logical steps would be: Start with the green screen key, but you immediately know you’ll need multiple keyers or advanced techniques to handle the green shirt without creating a hole in the character. You’ll likely pull a general key for the background but also need a separate, more solid “core” matte for the character’s main body, perhaps using a different keyer or even rotoscoping if necessary. You’ll also need to deal with the edge detail, particularly around hair and the blurred edges caused by motion. This involves refining the key’s matte, potentially using techniques to ‘despill’ the green bounce light off the character (removing the green tint that’s bled onto them) and carefully managing the semi-transparent areas of the motion blur. Simultaneously or concurrently, you’d track the camera movement from the green screen plate so your background street plate can be positioned and moved correctly behind the character. If the character is moving relative to the camera, you might need to track the character too, or track elements on them, to add effects that stick to their body. Once you have the character keyed and matted as cleanly as possible and the background tracked in, the integration begins. You analyze the lighting on the character and compare it to the lighting in the street plate. Does the character need more contrast? Is the key light coming from the right direction? You’d use color correction nodes to adjust the character’s luminance and color balance to match the street plate. You’d look at the shadows in the street plate – are they hard or soft? You’d need to create corresponding shadows for the character onto the street surface, ensuring they have the correct softness and direction. You’d then look at the atmospheric conditions of the street – is it hazy? Dusty? You’d add subtle atmospheric effects between the character and the background to push them into the scene and create depth, perhaps using the Z-depth pass if available or by manually grading based on distance. The lens flares and dust motes from the street plate also need consideration; perhaps some need to appear *in front* of the character, others behind. You’d use masks or mattes derived from your character element to ensure these artifacts layer correctly. Finally, you’d analyze the noise or grain in the street plate and add a matching amount and type to the entire combined shot to give it a consistent texture. This entire process, involving multiple layers, mattes, tracks, color corrections, and effects, isn’t just throwing things together; it’s a complex chain of logical steps, each addressing a specific problem in the pursuit of a seamless, believable final image. That, in a nutshell, is the iterative and multifaceted nature of applying The Logic of VFX Compositing to a challenging shot, requiring both technical skill and a sharp, analytical eye honed by experience.

Efficient Compositing Workflows

The Mindset of a Compositor

Beyond the tools and techniques, The Logic of VFX Compositing is really a mindset. It’s about having a critical eye. You constantly look for what’s wrong, what breaks the illusion. You scrutinize edges, check for color mismatches, watch the motion for hitches. It’s about paying attention to detail, even tiny things like a single pixel or a subtle shift in color.

It’s also about being a problem-solver. Every shot presents unique challenges. There’s no single magic button. You need to analyze the situation, figure out the best approach based on The Logic of VFX Compositing, and be prepared to experiment and iterate until you get it right. Sometimes the most elegant solution comes from combining simple tools in a clever way, guided by that underlying logic.

Communication is also key. You’re often working with directors, supervisors, 3D artists, and other team members. Being able to articulate *why* something isn’t working or *why* you need a specific element in a particular way is crucial. Explaining your approach based on The Logic of VFX Compositing helps everyone understand the challenges and goals.

Ultimately, The Logic of VFX Compositing is about storytelling through visuals. Our goal isn’t just to stick things together; it’s to help tell the story by creating visuals that support it without distracting the audience. If the composite is bad, it pulls the viewer out of the movie or show. If it’s good, they don’t even notice it’s there – the magic works. That’s the ultimate goal of applying The Logic of VFX Compositing.

In Conclusion (Using different words!)

So, while the software and techniques in VFX compositing continue to evolve at lightning speed, the core principles, The Logic of VFX Compositing, remains constant. It’s about understanding how images are built, how light and color behave, and how to seamlessly blend different elements together to create a convincing whole. It’s a blend of technical skill, artistic sensibility, and logical problem-solving.

Whether you’re just starting out or you’ve been doing this for years, constantly returning to and strengthening your understanding of The Logic of VFX Compositing will make you a better artist and a more effective problem-solver. It’s the foundation that allows you to tackle any shot, no matter how complex, and achieve results that truly sell the illusion.

It’s not just about making things look cool; it’s about making them look *real* (or intentionally unreal in a controlled way!). And that, my friends, is the true power and beauty of understanding The Logic of VFX Compositing.