The Symphony of a 3D Render

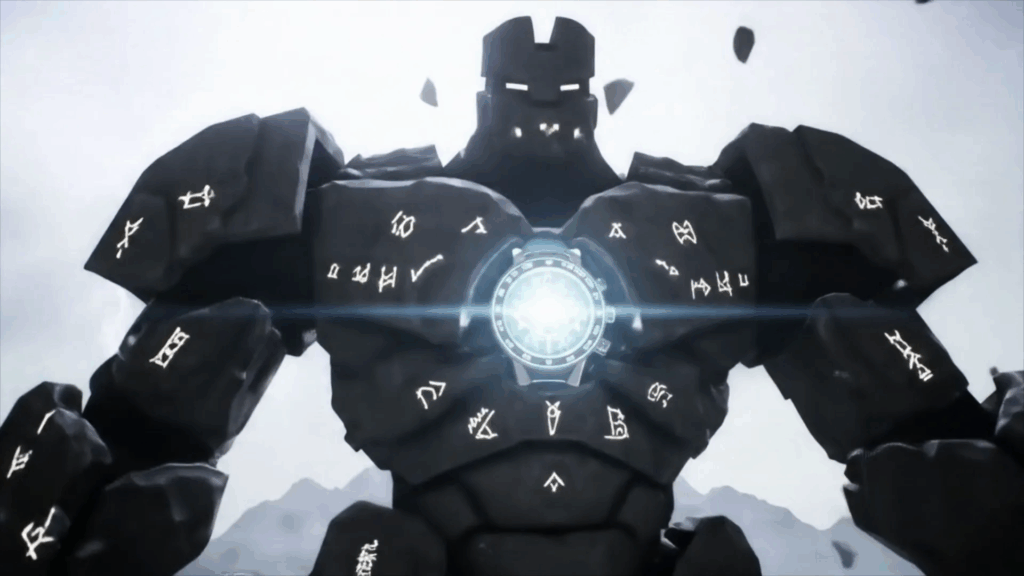

The Symphony of a 3D Render. It sounds kinda dramatic, right? Maybe a little over the top? But honestly, after spending years wrestling pixels, coaxing light, and building entire worlds inside a computer, that’s exactly what it feels like to me. It’s not just clicking a button and *poof* there’s an image. Nah, it’s way more involved. It’s a whole performance, a complex dance of different elements all coming together to create something visually stunning.

Think about it. You start with just an idea, maybe a sketch, maybe just a flicker in your brain. Then, piece by piece, you build it. You shape the objects, give them textures that tell a story – is it rough metal, smooth glass, soft fabric? You light the scene, not just throwing a lamp in there, but placing lights deliberately to highlight certain parts, cast dramatic shadows, or create a specific mood. You set up the camera, deciding what the viewer sees, what’s in focus, what’s blurry.

And then, finally, after all that setup, you hit that render button. That’s when the computer takes everything you’ve done – the models, the materials, the lights, the camera – and crunches the numbers, calculating how light bounces, how surfaces react, how everything should look from that specific viewpoint. It’s the grand finale, the moment the orchestra plays the whole score together. It’s The Symphony of a 3D Render.

I remember my first real render that I felt was… well, kinda good. It wasn’t fancy, just a simple still life, a couple of fruit bowls and a bottle on a table. But getting the glass of the bottle to look *right*, getting the light to catch the edges just so, making the fruit look edible… man, that took hours. Hours of tweaking, rendering little test squares, tweaking again. It felt like conducting a tiny orchestra, trying to get every instrument in tune.

This journey, from a blank digital canvas to a finished image, is what I want to talk about. It’s a process I’ve come to deeply appreciate, full of challenges, breakthroughs, and surprisingly creative moments. It’s not just technical; there’s a huge artistic side to it. Every decision, from the shape of an object to the intensity of a light, affects the final piece. It’s this blend of art and science that makes The Symphony of a 3D Render so captivating to work with.

The Maestro: Getting the Idea Rolling and Choosing Tools

Before any notes are played in The Symphony of a 3D Render, you need a maestro. That’s the artist. That’s me, sometimes, or maybe you if you’re diving into this world. It all starts with an idea. Where do ideas come from? Everywhere, honestly. A cool building I saw downtown, a weird dream, a story I read, or just a random thought like, “Hey, what would a robot made of rusty spoons look like?”

For me, the idea phase is often the most fluid and sometimes the most frustrating. You have this picture in your head, but how do you translate it into 3D space? Sometimes I’ll sketch it out, rough and messy, just to get the basic shapes down. Other times, I’ll gather reference images – photos of textures, environments, objects that inspire the mood or style I’m going for. Pinterest boards are my best friend during this stage. It’s about building a visual library for the concept.

Then comes the big decision: what tools do I use? This is like a musician choosing their instrument. There are tons of 3D software packages out there. Blender, Maya, 3ds Max, Cinema 4D, ZBrush, Substance Painter… the list goes on. Each has its strengths, its quirks, its loyal fanbase. Picking one can feel overwhelming at first.

When I was starting out, I remember trying a few different ones. It was like trying to learn three instruments at once! My advice? Pick one widely used program and stick with it for a while. Learn its basics inside and out. Don’t try to master everything at once. I ended up landing on Blender because it was free and incredibly powerful, with a massive community. That community part is huge – if you get stuck (and you will, believe me!), chances are someone else has had the same problem and there’s a tutorial or forum post about it.

Choosing your software is a personal journey. It depends on what kind of 3D work you want to do (animation, arch-viz, product renders, character art?), your budget, and what just *feels* right to you. It’s like finding your voice before you can even start writing The Symphony of a 3D Render.

Learn more about 3D software choices

The Orchestra: Building the World (Modeling)

Once the idea is solid and I’ve got my software fired up, it’s time to build the orchestra – the 3D models themselves. This is where the digital clay comes into play. Modeling is essentially sculpting in a 3D space. You start with basic shapes, like cubes, spheres, or cylinders, and you push, pull, extrude, bevel, and twist them until they resemble the objects you want to create.

Sculpting Digital Clay

There are different ways to model. “Polygonal modeling” is probably the most common for general objects. You work with faces, edges, and vertices (those little points where edges meet) to shape things. It’s very precise, like building with tiny LEGOs, but you can make incredibly complex forms. I remember trying to model my first detailed character – a simple robot. Getting the joints right, making the panels fit together cleanly… man, that took patience. Lots of undo button action!

Another method is “sculpting,” which is more like working with actual clay. Programs like ZBrush or even Blender’s sculpting tools let you use brushes to push and pull the surface of a mesh, adding fine details like wrinkles, dents, or muscle definition. This is awesome for organic shapes like characters or creatures. I love sculpting; it feels more intuitive, more artistic in a way, like my hands are shaping the digital form directly.

Keeping it Tidy (Topology Talk)

Now, here’s something that might sound technical but is super important: topology. In simple terms, it’s the arrangement of those faces, edges, and vertices on your model. You want clean, organized topology. Why? Because bad topology can make your model look weird when you try to smooth it, distort textures, or make it a nightmare to animate later on. Think of it like building a house with crooked walls – it’s just not going to hold up or look good.

Learning good topology took me a while. It’s not always the most fun part, but it’s crucial for a professional-looking result. You aim for mostly four-sided faces (quads) whenever possible. It makes the mesh behave predictably. I spent hours watching tutorials just on this topic, trying to understand the flow of edges around complex shapes like faces or hands. It’s like making sure all the instruments in The Symphony of a 3D Render are arranged correctly on stage – makes for a much smoother performance.

Adding Detail: The Micro-World

Modeling isn’t just about the big shapes. It’s also about the tiny details. Scratches on metal, wood grain texture molded into the surface, bolts holding plates together. You can model these things directly, but often it’s more efficient to use techniques like “normal mapping” or “displacement mapping” which we’ll talk about a bit more in the materials section. Still, the underlying model needs to have enough detail to support these textures without falling apart.

I learned the hard way that sometimes adding *too much* geometric detail too early can bog down your computer and make everything slow. It’s a balance. You need enough polygons to define the shape clearly, but not so many that your machine cries for mercy every time you try to move something. Optimizing models is a skill in itself, making sure your digital orchestra isn’t overloaded.

Building the models is the foundational work. It’s the stage and the performers before the lighting hits or the music starts. A well-modeled scene is the backbone of a great render. If your models are weak, the rest of the process is just trying to polish something fundamentally flawed. So, take your time here, build deliberately, and don’t be afraid to start over if you need to. I’ve scrapped entire models and rebuilt them cleaner, and it always paid off in the end for The Symphony of a 3D Render.

Discover the basics of 3D modeling

The Score: Giving Surfaces Life (Materials and Textures)

Okay, you’ve built your models. You’ve got the shapes of everything, but they look kinda… bland. Like gray plastic toys. This is where materials and textures come in – the score that tells the orchestra how to play, giving each element its unique sound and feel. Materials define how a surface looks and reacts to light. Is it shiny? Rough? Transparent? Does it glow? Textures are the images that add detail, color, patterns, and imperfections.

Giving Surfaces Personality

Setting up materials is a crucial part of making a render believable or visually interesting. You’re basically telling the computer the physical properties of a surface. You adjust sliders for things like “color” (the base color of the object), “specular” (how shiny it is), “roughness” (the opposite of shiny, how spread out reflections are), “metallic” (does it look like metal?), and “transmission” (is it see-through like glass?).

Getting materials right can be tricky. That glass bottle I mentioned earlier? Making the glass look like actual glass, with accurate reflections, refractions (how light bends as it passes through), and maybe a little bit of grunge or fingerprints… that took a lot of tweaking. It’s not just about making it look like glass; it’s about making it look like *that specific piece* of glass, with its history and imperfections. It adds realism and character.

I often spend a surprising amount of time just working on materials. Opening up a material editor can look intimidating at first, with nodes connected by wires, like a complicated flowchart. But each node represents a property or a texture, and connecting them is like building up the layers of a surface’s appearance. It’s incredibly powerful once you get the hang of it. You can create anything from polished chrome to weathered wood to glowing lava by mixing and matching these properties.

The Magic of Textures

While materials define the *type* of surface, textures add the *details* you see on it. These are basically 2D images mapped onto your 3D model. A brick wall texture, wood grain, scratches, dirt, logos – all these are textures. You can paint textures yourself, use photos, or find them on texture libraries.

But it’s not just about color! Textures can also control other material properties. A “roughness map,” for example, uses dark and light areas in an image to tell the renderer where the surface should be rougher (lighter areas) and where it should be shinier (darker areas). This is how you get subtle variations on a surface, like wear marks on a floor or fingerprints on glass. Similarly, “normal maps” or “bump maps” use textures to simulate bumps and dents on a flat surface without actually adding more geometry – a huge performance saver! Using these texture maps together is key to creating rich, detailed, and believable surfaces that make The Symphony of a 3D Render sing.

I remember working on a project that needed a really old, beaten-up metal look. Just applying a rusty texture wasn’t enough. I had to find or create separate textures for the base metal color, the rust patches, the scratches, the areas where paint had peeled, and even a roughness map to show where it was smooth from wear and where it was rough from corrosion. Layering all those textures and adjusting how the material nodes blended them together was a meticulous process, but the result was incredibly satisfying. The metal felt *real*, like it had a history.

Mapping it Out (UVs)

One hurdle you’ll face with textures is “UV mapping.” This is essentially like unfolding your 3D model into a flat 2D shape, like skinning an orange or flattening a cardboard box. Your 2D texture image is then placed on this flattened shape, and the software uses this map to figure out how to wrap the texture correctly back onto the 3D model. If your UVs are messed up, your textures will look stretched, squished, or cut off in weird places.

UV unwrapping can be tedious work, depending on the complexity of your model. For simple objects, it’s easy. For complex characters or intricate machinery, it can be a puzzle. You have to make cuts along the seams of your model to allow it to unfold cleanly, like cutting along seams on a piece of clothing to lay it flat. I used to dread UV unwrapping, but over time, I learned techniques to make it less painful. Good UVs are the foundation for good textures, and good textures are vital for a convincing render. They provide the fine details that bring the digital world to life and make The Symphony of a 3D Render visually rich.

Mastering 3D materials and textures

The Stage Lighting: Illuminating the Scene

You’ve built your models and given them materials and textures. Now, they’re just sitting there in a dark, empty void. This is where lighting comes in – arguably the most important element in making your render look good. Lighting isn’t just about making things visible; it’s about shaping the forms, creating depth, setting the mood, and guiding the viewer’s eye. It’s like the stage lighting for The Symphony of a 3D Render.

Sculpting with Light

Light in 3D works much like light in the real world, but you have total control. You can place lights anywhere, change their color, intensity, size, and shape. You can create soft shadows or sharp, dramatic ones. You can make a scene feel warm and inviting or cold and stark, just by changing the color and direction of your lights.

I learned pretty quickly that bad lighting can ruin even the best model and materials. A beautifully detailed object can look flat and boring under flat, even lighting. But place a light strategically, and you can highlight its curves, emphasize its textures, and make it pop. It’s like sculpting with light and shadow.

One of the first lighting setups people learn is the “three-point lighting” system, often used in portrait photography or product shots. You have a “key light” (the main, strongest light) that defines the shape and casts the main shadows. Then a “fill light” on the opposite side, softer and less intense, to lighten those shadows and reduce contrast. Finally, a “back light” or “rim light” placed behind the object to create a highlight along its edge, separating it from the background and adding depth. It’s a classic for a reason, and a great starting point for understanding how lights interact.

Different Lights, Different Moods

There are various types of lights in 3D software. “Point lights” are like bare light bulbs, emitting light in all directions from a single point. “Sun lights” simulate the sun, casting parallel rays and sharp shadows (great for outdoor scenes). “Area lights” simulate things like softboxes or windows, emitting light over a surface area, which gives softer shadows. “Spotlights” are like stage lights, casting a cone of light.

Beyond these basic types, you also have environment lighting. An “HDRI” (High Dynamic Range Image) is a 360-degree panoramic image that captures the lighting information of a real environment. You can use this to light your 3D scene as if it were placed in that environment – whether it’s a sunny field, a busy city street, or an indoor studio. Using HDRIs is incredibly powerful for creating realistic lighting and reflections.

I remember struggling with an interior scene for ages. It just felt dead. I had point lights and area lights everywhere, but it didn’t look right. Then someone suggested using an HDRI of an indoor environment. Instantly, the scene came alive! The ambient light from the image filled the room naturally, and the reflections on surfaces looked accurate. It was a lightbulb moment, literally and figuratively. It taught me that ambient light and subtle variations are just as important as the main light sources in creating a believable scene and completing The Symphony of a 3D Render.

Setting the Scene

Lighting is also deeply tied to the story or mood you want to convey. Bright, even lighting feels open and friendly. Dark, dramatic lighting with strong shadows feels mysterious or tense. Warm lights feel cozy; cool lights feel sterile or cold. You can use color and intensity to evoke specific emotions in the viewer.

Thinking about the source of light in your scene helps a lot. Is there a window? A lamp? A fire? Even if you’re placing artificial lights, grounding them with an implied source makes the lighting feel more natural and intentional. It’s about building a believable lighting narrative, just like a director uses lighting in a movie. You’re not just illuminating objects; you’re illuminating the scene’s story and ensuring every note of The Symphony of a 3D Render is heard clearly.

Shining a light on 3D illumination

The Camera Angle: What the Viewer Sees

Alright, you’ve built the world, textured it, and lit it beautifully. Now, how do you show it off? You need a camera! The camera in 3D is just like a real camera (or your phone camera, really). You position it in your scene, point it where you want, and tell it what to focus on. This stage is all about presentation – deciding what the audience sees and how they see it in The Symphony of a 3D Render.

Finding the Best View

Choosing the right camera angle is crucial for good composition. A low angle can make an object look imposing and powerful. A high angle can make it look small or vulnerable. A straight-on shot is more objective, while an angled shot can add dynamism. Think about what you want to emphasize. Is it the detailed texture of a surface? The overall shape of an object? The relationship between multiple objects?

Playing around with different camera positions and rotations is a must. Don’t just plop the camera down randomly. Take the time to move it around, look through its lens, and see how it changes the scene. Experiment with different focal lengths too. A wide-angle lens (lower focal length) will distort perspective, making things near the camera look bigger and things far away look smaller – great for grand landscapes or dynamic close-ups. A telephoto lens (higher focal length) compresses space and makes things look flatter – good for portraits or isolating a specific part of the scene.

I often find myself tweaking the camera right up until the final render. Even a small shift in angle can make a huge difference to the overall feeling of the image. It’s like finding the perfect seat in the concert hall for The Symphony of a 3D Render – you want the best view of the performance.

What to Focus On (Depth of Field)

Real cameras can focus on one thing and blur everything else. This is called “depth of field,” and you can simulate it in 3D. It’s a powerful tool for directing the viewer’s eye. By focusing on your main subject and blurring the background (or foreground), you immediately tell the viewer, “Look here!”

Getting depth of field right can add a lot of realism and artistic flair. A shallow depth of field (where only a small area is in focus) can isolate your subject and create a dreamy or cinematic look. A deep depth of field (where almost everything is in focus) is better for showing a whole scene clearly, like in architectural visualizations. It’s another layer of control you have over how the audience perceives your work.

Making it Look Good (Composition)

Beyond just placing the camera, there’s composition. This is the art of arranging the elements within the frame. Rules like the “rule of thirds” (imagining a tic-tac-toe grid over your image and placing points of interest along the lines or intersections) can help create more balanced and visually appealing layouts. Leading lines, negative space, framing elements – these are all principles from traditional art and photography that apply directly to 3D rendering.

I spent a good amount of time studying photography and film composition, and it completely changed how I set up my cameras in 3D. It’s not just about pointing the camera at the object; it’s about how the object sits within the frame, how it interacts with the background, and how the viewer’s eye is led through the image. A well-composed render feels intentional and professional. It helps the audience appreciate the entire picture of The Symphony of a 3D Render, not just individual elements.

Ultimately, the camera is your storyteller. It dictates what the viewer sees, what’s important, and the perspective they take on your digital world. Taking the time to carefully set up your camera, considering angle, focal length, depth of field, and composition, is just as important as creating the models and materials themselves. It’s the final touch before the performance truly begins.

Setting up your 3D camera like a pro

The Performance: The Render Engine at Work

Okay, everything is set. The models are built, the materials are applied, the lights are shining, and the camera is in position, waiting. You’ve conducted your digital orchestra. Now, it’s time for the actual performance – the rendering process. This is where the computer takes all the information you’ve given it and calculates the final 2D image. This process is handled by the “render engine,” the brain of The Symphony of a 3D Render.

The Calculation Engine

A render engine is a complex piece of software that simulates how light behaves in your 3D scene. It figures out where light rays come from, how they bounce off surfaces (which is determined by the materials!), how they pass through transparent objects, how they are absorbed, and ultimately, what color each tiny pixel in your final image should be.

There are different types of render engines, and they use different methods to do these calculations. Some common ones include “ray tracing” (or “path tracing”), which simulates light rays bouncing around, giving very realistic results, especially for reflections, refractions, and global illumination (light bouncing indirectly). Others use “rasterization,” which is faster but less physically accurate, often used in real-time applications like video games. For high-quality still renders or animations, ray tracing engines like Cycles (in Blender), V-Ray, Octane, or Redshift are popular choices because they can produce stunningly realistic images.

When I first started, I didn’t really understand what the render engine was doing. I just knew it was the thing that turned my 3D scene into a picture. But learning a bit about *how* it works, understanding concepts like samples (how many light paths it calculates per pixel), bounces (how many times light reflects or refracts), and noise (grainy artifacts that appear when there aren’t enough samples) helped me troubleshoot problems and optimize my render settings to get better results faster.

The Waiting Game

Rendering takes time. Sometimes a lot of time. Especially for complex scenes with lots of detailed models, intricate materials, soft shadows, and realistic lighting. Your computer’s processor (CPU) or graphics card (GPU) does the heavy lifting. More powerful hardware means faster renders.

I remember hitting the render button on that first complex scene and seeing the estimated time: “3 hours.” Three hours! For one still image! It felt like an eternity. This is the waiting game every 3D artist knows well. You watch those pixels slowly resolve, the noise gradually disappearing as the engine calculates more and more samples. Sometimes you see a mistake you made – a texture is off, a light is too strong – and you have to stop the render, fix it, and start all over. It’s a test of patience.

Learning to optimize your scene can dramatically reduce render times. Simple things like making sure objects outside the camera’s view aren’t being fully calculated, using simpler geometry where possible, and tweaking material settings can shave off significant time. Render farms (networks of computers dedicated to rendering) are also an option for big projects, though they cost money. For individual artists, it’s often about finding the balance between render quality and render speed that your hardware can handle reasonably. It’s about getting The Symphony of a 3D Render to finish its performance within a reasonable timeframe.

Picking the Right Brain

Just like choosing your main 3D software, selecting a render engine is a key decision. Some software comes with built-in engines (like Blender’s Cycles and Eevee). Others require you to buy or subscribe to external engines. Each engine has its own strengths, workflow, and performance characteristics. Some are better suited for realistic rendering, others for stylized looks, some are faster on CPUs, others on GPUs.

I’ve played around with a few different engines over the years. Switching engines can feel like learning a new language sometimes, as the settings and workflows are different. But understanding what different engines offer can help you pick the best tool for a specific project. If you need speed for animation previews, a faster, maybe less accurate engine might be better. If you need absolute photorealism for a product shot, a high-end path tracer is probably the way to go. The engine is the conductor that brings all the elements of The Symphony of a 3D Render together into the final visual piece.

Explore the magic behind render engines

The Final Mix: Polishing the Gem (Post-Processing)

You’ve waited, you’ve watched the pixels resolve, and finally, the render is finished! You’ve got your raw image. Are you done? Not usually! This is where post-processing comes in – the final mix and mastering of The Symphony of a 3D Render. It’s the step where you take the raw output from the render engine and give it that final polish to make it truly shine.

Polishing the Gem

Post-processing is typically done in 2D image editing software like Photoshop, GIMP, or even within the 3D software itself using compositor nodes. It’s where you make final adjustments that are often easier and faster to do after rendering than by tweaking settings in the 3D scene and re-rendering.

Color correction is a big part of this. You can adjust the overall brightness, contrast, color balance, and saturation. Maybe the render came out a little too warm, or the shadows are too dark. These are things you can easily fix in post. You can match the look and feel to a specific style or reference image.

I always do some level of color correction. Sometimes it’s subtle, just giving the colors a little more punch or adjusting the white balance. Other times, it’s more dramatic, like transforming a daytime render into a moody sunset scene (though doing as much as possible in 3D lighting is usually better for realism). It’s like tuning the final sound levels and adding effects to the recorded orchestra performance.

Adding Sparkle (Effects)

Post-processing is also where you add effects that are either difficult to achieve perfectly in 3D or are faster to apply in 2D. Things like bloom (the glow around bright lights), lens flares, depth of field (if you didn’t do it in the render engine, or want to enhance it), motion blur (for animations), vignettes (darkening the edges of the image), and even stylistic effects like chromatic aberration.

Adding bloom to highlights can make lights feel more intense and atmospheric. A subtle vignette can help focus the viewer’s eye towards the center of the image. Be careful not to overdo these effects, though! Too much bloom can make everything look blurry and blown out, and excessive lens flares can look cheesy. It’s about adding just enough to enhance the image, not distract from it. It’s adding those final flourishes and dynamics to The Symphony of a 3D Render.

Putting it All Together

Another powerful post-processing technique is compositing, especially if your render engine allows you to output different “render passes.” These are separate images that isolate different elements of the render, like the diffuse color, reflections, shadows, ambient occlusion, specularity, etc. In a compositor, you can combine these passes using nodes, giving you granular control over each element.

For example, you could render the diffuse color pass, a separate pass for reflections, and a pass for shadows. In post, you can then adjust the intensity of *just* the reflections or *just* the shadows without affecting the rest of the image. This is incredibly flexible for making fine adjustments without re-rendering the whole scene, which can save hours or even days of work. It’s like having separate tracks for violins, brass, and percussion, allowing the sound engineer to adjust each one individually in the final mix.

My post-processing workflow varies depending on the project, but it almost always involves some level of color correction and maybe a touch of bloom or vignette. For more complex scenes or animations, using render passes and compositing is essential for flexibility and efficiency. It’s the final stage where you refine everything, making sure every element of The Symphony of a 3D Render comes together harmoniously for the audience.

Refining your renders with post-processing

The Audience: Sharing Your Work

You’ve done it! You’ve taken an idea, built the models, applied materials, lit the scene, set the camera, rendered the image, and polished it in post. You’ve conducted and performed The Symphony of a 3D Render from start to finish. What’s left? Sharing it!

Putting your work out there can be exciting and a little nerve-wracking. You spent so much time on it, and now you’re showing it to the world. Sharing your renders on platforms like ArtStation, Behance, or even social media like Instagram is a great way to get feedback, connect with other artists, and build a portfolio.

Feedback is invaluable. It can be tough to hear criticism, especially when you’re attached to your work, but constructive feedback is how you improve. Someone might point out something you completely missed – a texture that looks blurry in one spot, a shadow that doesn’t make sense, or a composition that could be stronger. Learning to take feedback objectively is a crucial skill for growth as an artist. It helps you understand how your symphony is being received by the audience.

Sharing your work is also a way to document your progress. Looking back at my early renders compared to ones I’m doing now is a wild ride. You can see how much you’ve learned, how your style has evolved, and how you’ve gotten better at conducting that complex Symphony of a 3D Render.

Tips for sharing your 3D renders online

Conclusion

So there you have it. From that first spark of an idea to the final polished image, The Symphony of a 3D Render is a layered, intricate, and rewarding process. It involves creativity, technical skill, patience, and a whole lot of problem-solving. It’s not just about mastering software; it’s about understanding light, form, color, and composition, and bringing all those elements together in a digital space.

It’s a journey I’ve been on for a while now, and I’m still learning new things every day. The technology keeps evolving, and there are always new techniques to explore. But the core principles remain the same: start with a strong concept, build a solid foundation with your models, give them character with materials and textures, illuminate them thoughtfully with lighting, frame the view effectively with the camera, let the render engine do its magic, and give it a final polish in post.

Every project, big or small, feels like conducting a unique orchestra. There are moments of harmony and moments of discord, but when all the elements finally click into place, and that final image appears, it’s a truly satisfying feeling. The Symphony of a 3D Render is complete, and you get to share the music with the world.

If you’re thinking about getting into 3D, don’t be intimidated by the complexity. Start small, focus on one step at a time, and don’t be afraid to make mistakes. There are tons of resources out there, and a supportive community ready to help. It’s a challenging but incredibly fun and creative field. Maybe one day, you’ll be conducting your own spectacular Symphony of a 3D Render.

You can find more insights and perhaps see some examples of this symphony in action over at www.Alasali3D.com and specifically explore the detailed steps discussed here at www.Alasali3D/The Symphony of a 3D Render.com.